This post on influencing the flavor profile of roast coffee has been reviewed by Patrick Maloney of Maloney Coffee Consulting for accuracy.

At the end of the day, influencing the flavor profile of coffee during the roasting process involves much more than simply tossing the beans in a machine and hitting a button. Below, we take a dive into all the factors that go into influencing the flavor of each individual coffee.

Every roaster worth their salt knows that coffee offers one of the most complex tastes of any food or drink human beings consume. The coffee taster’s flavor wheel is even more complex than the tasting notes for wine, offering variations and sub-variations that include fruits, spices, teas, nuts, sugars, acids, vegetables, tobacco, and much more.

We know this, yet the question most roasters ask themselves ultimately comes down to how exactly we tease the flavors we want out of the beans we roast. It’s a simple question with complex answers, none of them right or wrong. Taste is subjective and roasting is half art, half science.

One person’s perfect cup is another’s least favorite.

Quick disclaimer: despite the breadth of information in this post, this is only a brief overview of the subject. Individual roasters use a range of techniques we don’t even touch on here, but this should give you a solid start.

What influences coffee bean flavor before the roasting stage?

Before we can really delve into how roasting specifically affects the flavor profile of coffee, we must explore everything that leads up to the roast. We’ll do our best to keep it brief, but you know how these things go. Onward!

Coffee Plant Varietals

When it comes to influencing the flavor profile of coffee, varietals matter. Just like wine grapes, coffee cherries come in different varieties, and each variety offers certain expected characteristics. We begin with the four main species of coffee: Arabica, Robusta, Excelsa, and Liberica.

Arabica is, of course, The Big One. It accounts for up to 60% of the world’s coffee production and is known for its brightness and fruit flavors. Its aromas are pleasant and can be quite complex. When most Americans think of the smell of brewed coffee, they’re thinking of Arabica. Many modern coffees are marketed as 100% Arabica due to the cultural preference for this varietal, for good or for ill.

However, not all Arabicas are created equal, as the classifications range from washed versus natural, honey process, FAQ (fair to average quality), Euro Prep, and more, all based on post-harvest processes in any given country of origin.

Higher elevation Arabicas produce different tastes than those grown at lower elevations, so on and so forth. You get the idea. No two coffees are ever the same in roasting or brewing.

Robusta is predominantly grown in Vietnam (90% of world’s production) and is known for its higher caffeine content and bold flavors, including notes of chocolate and nuttiness. It is less prone to defects and, if not roasted properly, can produce a more bitter and earthy aftertaste. It has an extensive and complicated history that includes elements of colonization, market oversaturation, production quality, political influence, and more.

Robusta is the main origin for many brands like Folgers, Chock Full O’ Nuts, and other “legacy” brands in supermarkets. In recent years, however, specialty coffee has seen a boom in Arabica coffees landing in supermarkets, making it much more accessible to the average shopper.

Excelsa and Liberica are difficult to separate, mostly because Excelsa was reclassified as a subvariety of Liberica despite their drastically different flavor profiles. Both species are seldom used globally and tend to be predominantly available in their growing countries. Where Excelsa is known for having a dark, tart fruitiness, Liberica can smell floral and fruity while tasting woody or even smokey. These varieties are frequently used in blends.

Environmental Factors

As with all great crafts, creating phenomenal coffee starts at origin. The flavor profile of each coffee begins in the very dirt in which it’s grown, the air flowing through its leaves, sun exposure, the altitude of the plants, the level of rainfall they receive, and numerous other factors. Each individual element gives every lot of coffee its unique terroir – the characteristic taste influenced by the environment where the coffee is produced.

Coffee, in its original state, is a fruit. Its journey from seed to cup consists of hundreds of steps. It can take anywhere from three to five years to see a coffee tree mature enough to harvest ripe cherries. It’s very likely the cup you drink today began its journey as a seedling in a faraway place almost a half-decade ago.

While the four main species of coffee listed above are the go-tos, they also include an incredible range of subvarieties, including hybrids of the above species or varietals known for specific locations or cultivation techniques. Some you may be familiar with include Typica, Bourbon, Caturra, and Geisha.

Each varietal offers its own flavor notes influenced by origin. If you’re seeking specific flavor notes, you must pay attention to the origin of your green coffee. You cannot create a specific tasting note during the roasting process if it doesn’t intrinsically exist in the origin itself. You can coax out various flavors, or mute some and accentuate others, based on your chosen roasting profile. However, if a coffee has no blackberry note at origin, you can’t introduce it in the roast or in the brewed cup.

Processing Factors

The ripeness of the coffee cherries is paramount in ensuring a quality cup of coffee at the end of the road. While it’s not impossible to craft a well-roasted coffee with beans from unripe cherries, industry standard dictates that the best coffee comes from ripe coffee cherries harvested at the right time. All specialty coffee must pass strict standards for importation or it can’t be called true “specialty grade coffee.”

Once the harvest cycle is complete, the coffee processing has only just begun. There are many more steps before the green beans are ready to be shipped to your favorite local roastery. Before you get to the bean, you must first figure out how each origin processes its harvest.

The how comes from a few distinct methods: natural process, washed process, and honey process, to name a few. There are other post-harvest methods, but for this blog we will stick with these three.

Natural process, or dry process, means the beans are dried in the original cherry over the course of weeks. The sugars from the fruit imbue the seeds (beans) with sweetness that follows through to the roasted counterpart.

Washed process, or wet process, is when the coffee fruit is immediately removed and the beans are, well, washed. This removes the pulp and mucilage before drying, which usually results in a “cleaner,” crisper flavor.

Honey processed beans are their own unique animal. Honey processing is a bit of a happy medium between the wet and dry processes, with the fruit and pulp of the coffee cherry removed but the mucilage left intact to dry with the bean. This type of processing results in coffees with lingering fruit sugars and sweetness, but less than you’d find in natural process.

You can go on a really deep dive into the different subtypes of honey processed coffee, but we’ll leave that to someone who already wrote that post (click that link).

Green Coffee Storage

One last factor that influences the flavor profile of coffee before it even hits the roaster is green bean storage. While green coffee is typically considered “fresh” for up to twelve months past harvest, storage factors can alter that timeline.

Temperature, light level, moisture level, and time will all affect green coffee beans. Roasted coffee is only as good as the green beans used, so it’s vital to make sure your green coffee is roasted before it begins losing some of its more delicate flavors, and definitely before it starts tasting, well, old.

Green coffee that hasn’t been stored well at origin or in a roastery can taste flat, musty, or even moldy. Green coffee beans are very porous, so a roaster must keep environmental factors in mind. Anything you keep around your green coffee could very well end up in the flavor profile, and not in a good way.

Roasting Up a Desirable Coffee Flavor Profile

To an experienced roaster, the above information will be old news. Even so, the refresher is important, because we must remember that building the desired flavor profile starts at the very beginning.

After you’ve done the initial legwork to find the perfect green coffee processed in a way that will highlight the notes you’re aiming for, it’s time to start thinking about how the coffee roasting process can further influence the flavor profile of coffee to get the results you want. Now it’s time to ask yourself the big questions.

Can you change the flavor of coffee depending on how it’s roasted?

The simple answer is yes, you absolutely can. Without wading too deep into the weeds on the chemistry of roasting, suffice to say the science of cooking also applies to the science of coffee roasting.

Which means, in a nutshell, that the Maillard Reaction is real.

The Maillard Reaction is the “browning” process for the things we consume, from coffee to meat to bread. It doesn’t only affect color, however. Food that has undergone this reaction has a unique flavor that can’t be replicated by other means.

That said, the level to which the browning reaction is applied to coffee is unique. Coffee beans undergo roughly 150 chemical processes during roasting, including expansion and what is known as “first crack” and/or “second crack.”

First crack occurs when free water is converted to steam inside the cell structure and beans become “exothermic,” or give off heat. Prior to this stage, the beans have gone through an initial drying phase during the first third of roast, absorbing heat (“endothermic”) before progressing through the aforementioned “Maillard Reaction.” After first crack is finished, the roast enters “Development Time,” which is where complex carbohydrates are broken down, sugars are caramelized, and various acids develop which contribute to coffee’s overall taste.

Second crack is typically when you get the coffee to a full medium roast and beyond towards a darker roast. Careful manipulation of these processes can dramatically alter the flavor of the roasted coffee.

If a dark roast is improperly done, the taste becomes “burnt,” a common refrain as a tasting note, resulting in the unpleasant carbon flavor we associate with overcooked food.

It’s safe to assume that few roasters want to burn or scorch the coffee. They do, however, want to brown the coffee.

What’s the deal with coffee bean color?

Coffee goes through several stages while roasting – green, yellow, cinnamon (light brown), brown.

Green coffee is coffee in its “raw,” unroasted state. This is what’s loaded into the roaster.

Yellow coffee is beginning to show signs of applied heat. It’s beginning to roast. The beans aren’t typically ready at this stage, but they are starting to undergo some of the necessary chemical processes.

Cinnamon, or light brown, coffee is likely nearing first crack. If you are aiming for a lighter roast, this is where you really need to start paying attention. Note that production coffee should go through first crack, even if you’re roasting a very light coffee, because first crack is when the bean releases moisture and begins developing sweetness. Stop the roast too early and you may end up with an underdeveloped and frankly undrinkable coffee. That said… white roasts do exist.

Brown coffee that has gone through first crack is on its way toward becoming either a light, medium, or dark roast. Note that this is where a lot of the art of roasting comes into play and where many of the decisions you make will impact the flavor of the coffee during the roasting process. This is where you decide in the development stage (past first crack to X finish point) which profile best suits either a coffee’s best potential or what satisfies your customers.

A coffee ought to get through first crack to be “finished,” especially if your goal is a very light roast. At this point, you have to decide how you’ll apply heat and air in order to finish your roast. Taking a coffee out before first crack completes happens in sample roasting, but very rarely in production roasting, simply because scientifically coffee needs enough time to develop without being too grassy or underdeveloped in the cup.

How does the darkness of the roast impact coffee flavor?

Light Roast Coffee

A lightly roasted coffee is a relatively new addition to the mainstream coffee world (though some cultures have lightly roasted coffee for centuries), and despite Starbucks coining the term “blonde roast” to describe it, it’s actually closer to cinnamon or light brown in color. Usually. The defining flavor profiles of lighter roasts are commonly called bright, acidic, and clean. They may highlight lighter and more delicate notes like florals or berries.

With lighter roasts, the oils from inside the bean aren’t released, so the beans might still have some wrinkles or “striations” on the surface and not appear oily. Brew color of light roasts is also lighter and some very light roasted Ethiopian coffees have been compared to tea.

The body of a light roast is, to be redundant, light. It would not be described as thick or heavy. For many coffee drinkers, light roasts are their go-to choice for interesting and enjoyable coffees. Other drinkers find them too acidic and off-putting for their taste. They don’t taste like what we traditionally associate with “coffee,” a.k.a. the dark roasts many people were raised on.

Medium Roast Coffee

A medium roast, also known as “city” or “full city” roast in some circles, is coffee that is roasted to just before or right at second crack, in the loosest sense. To dial this roast level in, there are levels of medium that affect flavor which take practice and experimentation to bring out the exact notes you’re looking for in the final cup.

Medium roasted coffees are known for walking the line between light and dark roasts. They typically bring in sweeter flavors, like chocolate and caramel, while maintaining some of the complexity and acidity of lighter roasts.

These coffees are often well-liked by a range of coffee drinkers who appreciate elements of lighter and darker roasts but don’t necessarily love either style on its own. It’s possible to maintain bright fruit and other delicate flavors while giving the coffee a more well-rounded body with comforting brown sugar and cocoa notes, as well as some spice flavors like cinnamon, clove, or even pepper.

Again, there is not one set stopping point for a medium roast. Medium roasts can be slightly lighter or darker depending on which flavors you’re trying to highlight most and it changes from origin to origin. Oils from the beans are typically not present on the surface unless you’re edging into a darker roast.

Dark Roast Coffee

Ah, the dark roast. Beyond the coffee industry, these are the coffees most people associate with their daily cup – black, rich, sweet, maybe even bitter or charred. These beans are dark to very dark brown and appear shiny due to the oils released after second crack. The amount of oil can vary depending on how dark a roast you’re dealing with and how many lipids and fatty acids were present in the green coffee.

Coffees roasted in a dark style tend to lose specific origin flavors, especially if those flavors are more delicate. However, they gain a level of sweetness and depth. When done well, dark roasts can possess hints of chocolate and produce a “hint of char” without over-carbonization. At a certain dark roast level, a “roasty” note can present itself, which is not always a bad thing.

A lot of modern industry opinion tends to consider darker roasts inferior for a host of reasons – it hides the coffee’s “true” flavor, it’s burnt, it’s too bitter, it’s what you do with lesser quality beans, etc. This can be a short-sighted view and an experienced roaster knows exactly when a dark roast is right.

From here, you can delve into the really dark side of the spectrum – French and Italian roasts, the two darkest style roasts you’re going to find for sale. These coffees are known for strong, bitter, smoky, and sometimes “burnt” flavors. While many Americans shy away from these roasts today, they remain very popular in their countries of origin.

How does First Crack affect coffee flavor?

We touched on first crack above. First crack is, of course, the stage during which the residual moisture in the green coffee expands until it “cracks,” resulting in a sound likened to popping popcorn.

As far as influencing the flavor profile of your selected coffee beans, the most important thing to remember about first crack is that sweetness starts to develop just after this point and the beans move from the light to light-medium to full medium and beyond.

Dropping coffee soon after first crack will result in much lighter roasts with more acidity and origin flavors. You’ll taste more citrus, floral, tropical, and bright notes. Waiting and properly maintaining heat after first crack will result in more sweetness and less acid, with more spice, nut, dark fruit, and confectionery notes coming forward.

It should also be noted that first crack doesn’t always happen at the same time, frequently determined by the specific type of machine you roast on. Each roaster makes a choice for how quickly and consistently they apply heat to reach that stage. Something as simple as roasting at a slightly lower temperature climb to delay first crack can also change the flavor profile of coffee.

Fine-tuning this aspect to obtain the flavors you’re aiming for will take time and experimentation, but it’s worth it. Each phase in roasting, from drying to Maillard to Development Time to how heat is applied throughout the roast, affects the final product.

How does Second Crack affect coffee flavor?

“Second crack” marks the progression from medium to dark roasts. It’s a slighter more discernible-sounding crack, and when the coffee hits a cooler tray at or past second crack, it can sometimes be called a “rolling crack” because it seems continuous. Part of that effect is the temperature differential between the very hot roast chamber and hitting the cooling tray and the ambient air.

This is when the carbon dioxide and other gasses still present in the bean break through the drier, more fragile structure. This “degassing” phase can take up to several days to complete inside a coffee bag or stored container.

Once a coffee reaches second crack, it must be closely monitored for the desired result. Coffee at this stage can rapidly go from dark to straight-up burnt depending on the time and heat level.

That said, this is the stage to aim for if you’re going for a darker roast with all those lovely, deep, sweet notes like chocolate, maple, caramel, nuts, or spices.

Be mindful that taking a roast past second crack will drastically reduce the acidity and some of the original flavor notes inherent in the beans, but not all. A general rule of thumb is that the longer you roast a coffee, the more you “mute” the brightness and fruit-forward notes while accentuating others, like chocolate and caramel. As with all things, there are tradeoffs for every choice made.

How does heat level affect the coffee roasting process?

Heat and proper airflow are directly responsible for the rate at which coffee darkens. An obvious answer, maybe, but an important one.

To go into greater detail, the application of heat has a great deal of impact on drawing out the flavors of coffee because it can be manipulated to roast the beans slowly or quickly. Rapidly rising temperatures can cause uneven roasting, much in the way that turning the heat up too high on the stove wouldn’t cook your food any faster – it would cause your food to burn on the outside before the inside is fully cooked. On the flip side, a very slow rise in temperature can result in an overextended roast time that brings out undesirable flavors.

Commonly, early in the roast (around and just after first crack), the exterior of the bean ends up darker than the interior, which can result in an imbalanced cup once the coffee is ground. It’s not a deal-breaker – many great coffees look lighter ground than they do in whole bean form. Even so, bear in mind that the color of the grounds will give you much needed information about how your roast profile affects the flavor in the final cup.

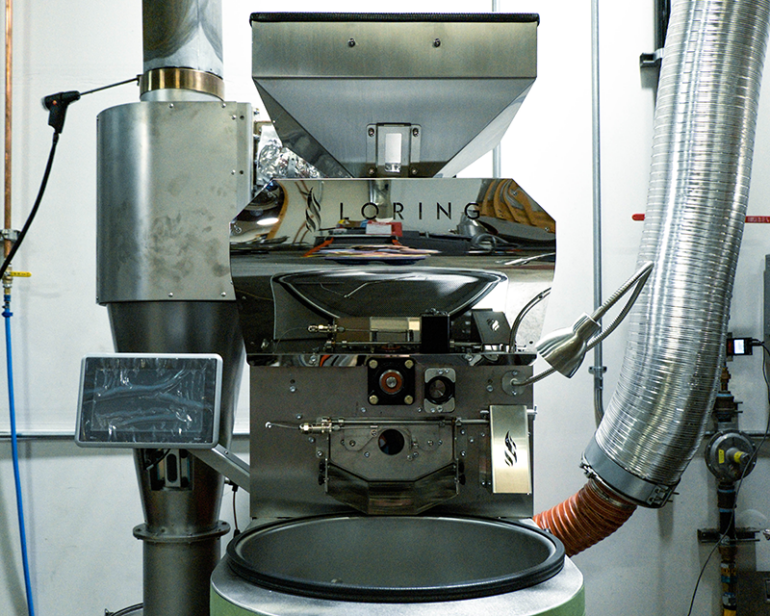

The key is in using equipment that applies heat consistently and offers a reliable amount of temperature control. This way, you can influence the rate at which your coffee beans reach each stage of the roast to tease out the flavor profile you’re targeting.

Does coffee roaster airflow matter for flavor manipulation?

It sure does. Airflow is how you manage and help properly maintain the heat used to roast the beans. Your roast profiling software should help you review and manage your roast curves so you can see where you need adjustments to hit the temperatures you want when you want to hit them.

Consistent, well-maintained airflow means consistent, well-maintained heat throughout the roasting process. If you’re unfamiliar with the temperature ranges necessary to hit the crack stages or the yellowing stage, it should be a key area of study. Using a roaster that offers exceptional control over your burner and fan speeds will help you put out consistent roasts once you find a profile you like.

Understanding how to work with the airflow of your roaster is essential for ensuring your roast is as uniform as you can make it and the beans aren’t being scorched by excessive application of heat.

How does blending coffee beans affect the flavor profile?

If there are two varieties or subvarieties of coffee you think would play well together, you can absolutely blend them to create any number of different flavor profiles.

We haven’t spoken much on the subject of blends in this post. Choosing between blends or single origin coffees is a personal decision for every roaster and depends entirely on their individual vision. Many roasters offer both options. Blending is certainly a way to introduce flavors from one lot to another in a way that produces a favorable result.

For example, you may roast two coffees with different profiles to the same darkness. One might be mellow, smooth, and sweet. The other might be more fruit-forward with a distinct spice note. Separately, they might taste a bit flat to your palate. But together, blended in the right quantities, they may play off each other beautifully and result in a more well-rounded coffee.

Both pre and post-roast blending offer very interesting ways to have flavors in coffee compliment each other, and perhaps access a wider customer base.

In Coffee Conclusion

We hope this primer on how to influence the flavor profile of coffee during the roasting process offered some valuable insight. As we mentioned in our disclaimer at the very start, this post only briefly touched on many of the factors that go into building your preferred roast profile.

In the future, we’ll take some deeper dives into the nitty-gritty, but in the meantime, we wish you all the best in exploring the world of coffee roasting and finding the flavor profiles that speak to you.

Remember: coffee roasting is an ever-evolving science and art. Whatever your vision, whatever your taste, there is space at the table for you.

For a truly in-depth guide to coffee roasting at the scientific and molecular level, we highly recommend Rob Hoos’ book, Modulating the Flavor Profile of Coffee: One Roaster’s Manifesto.

Questions? Let us know!